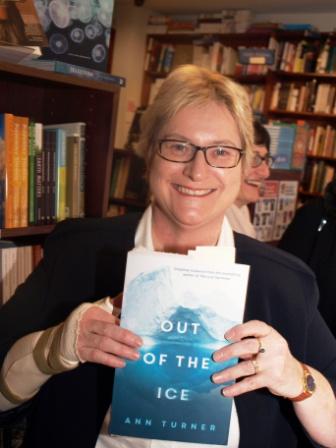

What better way to mark the beginning of winter on 1 June (and the return of nippy weather to Melbourne after a long Indian summer) than with the launch of Ann Turner’s new Antarctic thriller, Out of the Ice (Simon & Schuster. Ann joined Sisters in Crime when her first novel, The Lost Swimmer, was published last year. The launcher, script editor Annette Blonski, is also member of Sisters in Crime and delivered an insightful speech to a packed audience at Readings Carlton.

Annette Blonski (pictured right): Last year, here in Readings, I had the great pleasure of launching Ann’s first, and I’m delighted to say, very successful novel, The Lost Swimmer.

At the end of proceedings I mentioned that having read The Lost Swimmer, we had much to look forward to in Ann’s next book, Out of the Ice, also to be published by Simon & Schuster and due to be released in 2016. Here we are, a year later almost to the day, doing just that. Out of the Ice has fulfilled its promise, and more.

It may seem that Ann has produced two novels in quick succession but in truth, Out of the Ice has its origins many, many years ago. Ann wrote a screenplay simply titled, Antarctica, in the early days of her career as a filmmaker and gave me the script to read. I can’t remember whether she already knew I was obsessed with Antarctica, or whether she discovered it afterwards. Either way, you could say it was a shared obsession.

The script, Antarctica, was a very scary thriller and Out of the Ice is equally gripping and enthralling. The two stories – the screenplay and the novel – are however quite different, but the passion for this almost pristine wilderness (you could ask, is there anywhere on earth that is pristine?) informs both.

Antarctica’s beauty is not the comforting, soothing beauty of, say, a rainforest but through the eyes of Ann’s protagonist Laura it is breath-taking. The grandeur of its expanses, the colours of the ocean and the ice, the exhilaration of being so close to the penguins and the seals and Laura’s beloved whales, in Out of the Ice, this is a place where we humans come face to face with our limits and our limitations. It tests us and makes us humble. Well, at least some of us.

And so the story begins: with a mystery at its heart and a thrilling race against time to find the truth of what is really happening in a British base called Alliance, to which Laura is temporarily assigned.

While beautiful the Antarctic continent is a dangerous place but Laura Alvarado is an old hand in the Antarctica and she is our guide in this story. Science is not just her profession. It is her calling.

Ann has once again given us a compelling first person narrator. Laura is a rather endearing combination of exacting scientist and a woman with a pronounced weakness for good-looking men. She disarms the reader with her candour about the effect a pair of clear blue eyes and a winning smile can have. She is direct, sometimes downright tactless, endearing, ethical, and above all, funny.

Life has not been that easy for Laura. She has a testy relationship with her mother – something many daughters and mothers can relate to – and she hasn’t seen her father for years, not since her parents divorced. He is also a scientist, and Laura, despite her mother’s assessment of him, regards him as something of a hero. Her own record of relationships is, shall we say, complicated, and she’s managed to upset a few of her colleagues in the past by exposing some very serious malpractice. So she’s someone to be reckoned with when things are not quite right.

Laura has been commissioned to do an Environmental Impact Assessment of Fredelighaven, a former whaling station built by Norwegian whalers and abandoned many years ago to the elements. It’s about 30 minutes away from a British base called Alliance. When she arrives at Alliance she’s very surprised by how luxurious it is, given how comparatively basic the Australian bases are. A lot of money has been spent on this research facility. Another thing she is not used to is the hostility she experiences the minute she arrives. Large areas of the base are off-limits and the secrecy surrounding their activities is unnerving. The men here – and they’re all men – make it clear they’re not happy she is there. Except for one, Travis, and yes, he has beautiful blue eyes.

Pressure is mounting to bring tourists to Antarctica in greater numbers and the beautiful houses and the perfectly preserved, but grisly, processing plants make an ideal tourist destination. Laura is appalled. She hates tourists. But she is first and foremost a scientist so she will do her job and determine whether indeed this is a suitable location for tourism or whether it should be locked away forever.

Fredelighaven would not be the first whaling station to become a museum. They are major tourism destinations. Most countries have abandoned whaling. We now have a profound horror of it. But Norway, Greenland, Iceland and Japan, all continue to hunt whales. A museum can act as a cautionary tale. The Whaling Museum at Albany, WA is one such place. I recall that a few years ago on a holiday in Albany, I mentioned to the hosts of the B&B where I was staying that we would pay it a visit. Sally, one of our hosts, had vivid memories of going on a school excursion, in primary school no less, to the whaling station which was still in operation. It closed in 1978. It left a scar and to this day she recalls the smell. The smell of death.

Now you exit via the gift shop where the first thing you see is the rack of T-shirts emblazoned with Sea Shepherd on the front.

Fredelighaven, however, is not Albany. It sits alone, abandoned, in the wilderness.

On Laura’s very first visit there, she experiences something very unusual. Around the Australian bases, the Adelie penguins largely ignore the humans who study them or wander among them. They are relaxed in human company. Here, however, Laura is confronted with penguins who are not only apparently frightened by her presence, but they attack her, ripping into her gloves and her clothing, drawing blood.

Laura’s concerns about opening up the wilderness to even more tourism are given very concrete form in this scene. Contact with humans has the potential to damage the creatures who live there and whose home this is. But it’s more than that because Laura knows from her own experience and from a powerful bond she has developed with a whale she has named Lev, that it is possible to live in harmony with the wildlife of the Antarctica. Something seriously wrong is happening here.

She knows also from bitter experience prior to the arrival of her friend and fellow scientist, Kate, that she has been targeted. The impact study at Fredelighaven station is not supported by Alliance. They want her gone, and as quickly as possible.

Undeterred, Laura and Kate decide they must return to Fredelighaven. They realise they need to dive to see if something is happening offshore. This is when Laura sees something so unexpected and so shocking that it completely unnerves her.

When Laura and Kate start their dive, they make sure they stay close by each other’s side. This is protocol and it is a way of ensuring they stay safe. Then, a pod of whales appears before Laura’s eyes and she is mesmerised. A mother and baby swim close by and she can caress them as they roll above her, playing. It is then, rousing herself from the joy of this encounter, that she realises that she and Kate have become separated. Trying to control her panic, she starts to look for Kate. Pulled by a very powerful current she eventually finds herself near an ice wall. She manages to avoid the danger and in doing so discovers an ice cave. It is so tall and deep, the largest cave she has ever come across in Antarctica, that she can stand up in it. She takes off some of her gear and leaves it at the entrance so that, she hopes, Kate will know she is there. Then, everything changes.

“I stopped in shock. Behind an icy wall, clear and translucent, stood a boy, tousled dark hair, huge brown eyes, skinny arms raised high. He was calling to me through the ice, trapped like an insect in amber. All I could hear was the gentle splashing of waves, but I could see his mouth open wide in a yell. ‘Help me!’ He pounded his hands against the ice. ‘Help!’ Then as quickly as he appeared, he was gone.”

Was there a boy in the ice cave? Is this a figment of Laura’s imagination, a projection of her desire, her longing for family? Though we trust Laura, we the reader, her friend Kate and later Georgia, her boss, are not entirely sure that she is right. When Kate finds Laura, she tells her that she hasn’t seen the pod of whales Laura had been so entranced by, let alone a boy. Laura begins to doubt herself. Perhaps it is her imagination? Perhaps she really is toasty? In another part of the world, if someone were ‘toasty’ we’d call it, going troppo.

Laura however is not so easily swayed. If there is a boy here, in Antarctica, why is he here? What is he doing in the ice cave? Why is he crying for help? Maybe this really is happening. If so, something very strange, something terrible, is happening at Fredelighaven and at Alliance.

Laura’s quest begins therefore as an attempt to work out what is really going on at Base Alliance and Fredelighaven. In the process, Laura and the reader will come face to face with some of the pressing troubles and debates of our era.

It is no accident that Laura is profoundly engaged with studying an environment where the migratory patterns of the penguins and the whales are so crucial to their survival and the ecosystem of which they are apart. She herself is the product, if you will, of the waves of migration that characterised the 20th century and still convulse the world. Her Spanish mother lives in suburban Kew, half-way around the world from her childhood home, separated from her family and her culture. They in turn had been victims of the Spanish Civil War and each generation bears the scars of conflict, not just physically but psychologically.

Even with this background and this knowledge, the terrible secrets that Laura uncovers in her quest will take her way out of her comfort zone and into a dark world of a different kind of human migration, one she really had no idea existed. It will bring her face to face with her demons and make her question her own image of what family means and what her own family could look like. Along the way, the novel’s engagement with the environment, with wilderness, with migration, the most difficult, challenging and arguably significant issues of our day, are woven into the fabric of Laura’s journey.

It takes her from the ice cave of Antarctica to the wintry landscape of Nantucket, from the glow of a Nantucket Inn sheltering from winter storms and tucked into the maternal embrace of her hosts Nancy and Helen, to the nightmarish revelations and loss in Venice, and finally, beneath the ice once more in Antarctica.

Where The Lost Swimmer was set in warm sunshine, whether here in Australia or on the Amalfi coast in Italy, Out of the Ice is all about the bracing challenge of the cold and the race to preserve this very special place from harm. Laura is a woman of her time and just the person to help us succeed in that endeavour. I hope you enjoy her story as much as I did and I commend it to you wholeheartedly.

And the very good news is that Simon & Schuster have commissioned Ann to write two more novels, so there is much to look forward to!

Note: Ann Turner will be joining L A Larkin and Hazel Edwards for a Sisters in Crime event: Antarctic Noir: The Ice Women Cometh! Antarctic Noir: The Ice Women Cometh! October 7 @ 8:00 pm – 10:00 pm at the Rising Sun Hotel http://www.sistersincrime.org.au/event/antarctic-noir-the-ice-women-cometh/