Author: Judith Flanders

Publisher: Alison and Busby

Copyright Year: 2014

Review By: Robyn Walton

Book Synopsis:

t’s just another day at the office for London book editor Samantha “Sam” Clair. Checking jacket copy for howlers, wondering how to break it to her star novelist that her latest effort is utterly unpublishable, lunch scheduled with gossipy author Kit Lowell, whose new book will dish the juicy dirt on a recent fashion industry scandal. Little does she know the trouble Kit’s book will cause-before it even goes to print. When police Inspector Field turns up at the venerable offices of Timmins & Ross, asking questions about a package addressed to Sam, she knows something is wrong. Now Sam’s nine-to-five life is turned upside down as she finds herself propelled into a criminal investigation. Someone doesn’t want Kit’s manuscript published and unless Sam can put the pieces together in time, they’ll do anything to stop it.

Sam Clair is a middle-aged editor of middle-brow books and the occasional riskier exposé. After entangling herself in a criminal intrigue revealed by one of her authors, Sam muddles through with the help of three allies: her mother, who’s a powerhouse of a city lawyer; a CID cop, who becomes her lover; and an elderly neighbour, who’s there for her when danger comes close to home. Sounds like a formulaic cosy? Yes, but not 100% so. The smart-mouthed tone of Flanders’ narration supplies a bigger quotient of word-based witticisms, satire and sarcasm than we commonly encounter in cosies. This is cosy meets mean. Sam doesn’t walk the mean streets so much as mouth off about everything from lanes to boulevards. She amuses herself in the process: ‘If you paid attention to all the put-upon people in England, you’d never have time to be put-upon yourself, which would take all the fun out of things.’

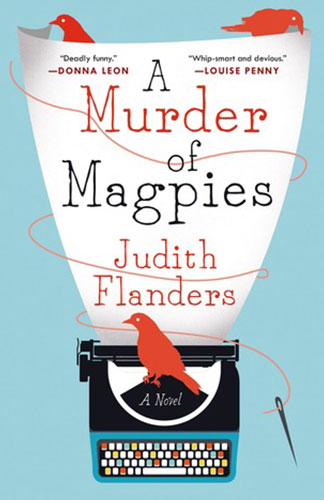

This novel was initially released in 2014, under the title Writers’ Block, before being reissued in early 2015 as A Murder of Magpies ahead of the release of Flanders’ second Sam Clair novel, A Bed of Scorpions. The delicate cover illustrations and pastel colours of the 2015 pair of books represent them as cosies, and that’s more accurate than the original packaging of the first title: it featured a gun and was strong on black and primary colours. Thankfully, for the sake of truth in advertising, the 2015 covers’ visual lightness is balanced by quotes classing the texts as capers which are ‘mordantly funny’ and ‘whip-smart’.

So far as I know, A Murder of Magpies (aka Writers’ Block) is Judith Flanders’ first crime fiction publication. She has previously published social history. Brought up in Canada but now living in London, Flanders takes a detached view of English urban life. Many of Sam’s targets are easy ones and the wisecracks none too fresh. Here’s a sample. Sam is being taken to the Reform Club for a confidential consultation about missing fashion industry author Kit.

‘It’s quiet,’ [Sam’s companion tells her] ‘but that’s because all the members are dead or deaf: either suits our purposes.’ He was right, so I followed him in. … It was very dark, very upholstered, very hushed: if you saw it in a movie you would think it was a parody of a gentleman’s club. No one in the room had ever heard of Kit, or fashion, although from a quick guess at the price of some of their suits, quite a few knew about money laundering. But they were too far away to worry about, and anyway, they hadn’t heard anything except the sounds of their own voices for decades.

As that reference to money laundering suggests, this is a novel about organised financial crime, with incidental disappearances and killings. As Sam remarks 20 pages in, when considering possible libel suits designed to suppress Kit’s latest tell-all exposé: ‘All fashion stories are stories of money and excess. And money and fame. And money.’ She sums up the gist of Kit’s manuscript revelations in words which make the crime and its cover-up seem ho-hum in the eyes of the worldly-wise: ‘It was a money-laundering operation on a major scale … Everyone knew. Only no one did.’ Sam then spends many more hours forensically going through documents at her mother’s kitchen table than attending Paris fashion shows. Unfortunately, her knowingness does not translate into sufficient explication: the narrative’s references to banks, lawyers, company directors and other players and entities are so confusing that I might have given up reading if it weren’t for the onward pull of Sam’s first-person narration.

The novel’s uneasy medley of plotting and comedy affects the narrative treatment of human casualties. If you find Sam’s absence of sentiment discomforting, you need to recall her stated preference for finding fun in self-centred complaining. Like the classic clown, Sam wisecracks in company and cries alone. In the opening chapter another author might have taken us to the scene of the road death of the courier believed to be carrying Kit’s manuscript to Sam’s office; he or she might have played on our emotions. Flanders chooses to leave that killing at a distance. The victim has no name, and Sam’s response when told of his death is to first ask ‘How do I come into this?’ A minute later Sam is snorting derisively and delivering a funny monologue about her authors’ reluctance to meet deadlines. The nice-looking cop on the receiving end of Sam’s humour routine is unsentimental too. As Sam perceives their interaction:

… I was both amusing and annoying him. He wanted boxes to tick. Don’t we all, Sunshine, I told him. But only in my head. Outwardly I tried to look sympathetic and helpful, not merely curious and simultaneously wanting to go away so I could get to my meeting.

As Flanders intuits, speaking through her protagonist, readers are likely to find her novel both amusing and annoying. My verdict: more amusing than annoying.