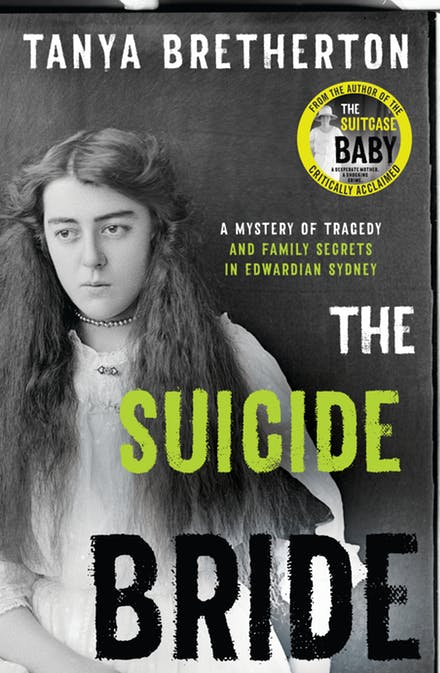

Author: Tanya Bretherton

Publisher/Year: Hachette Australia/2019

Publisher overview

From the author of the acclaimed THE SUITCASE BABY – shortlisted for the Ned Kelly and Nib awards – comes the chilling story of a charlatan, a murder-suicide, and a family tree so twisted that it sprouts monsters.

Whenever society produces a depraved criminal, we wonder: is it nature or is it nurture?

When the charlatan Alicks Sly murdered his wife, Ellie, and killed himself with a cut-throat razor in a house in Sydney’s Newtown in early 1904, he set off a chain of events that could answer that question. He also left behind mysteries that might never be solved. Sociologist Dr Tanya Bretherton traces the brutal story of Ellie, one of many suicide brides in turn-of-the-century Sydney; of her husband, Alicks, and his family; and their three orphaned sons, adrift in the world.

From the author of the acclaimed THE SUITCASE BABY – shortlisted for the 2018 Ned Kelly Award, Danger Prize and Waverley Library ‘Nib’ Award – comes another riveting true-crime case from Australia’s dark past. THE SUICIDE BRIDE is a masterful exploration of criminality, insanity, violence and bloody family ties in bleak, post-Victorian Sydney.

Reviewer: Jane E. Lee

On 12 January 1904, three young brothers awoke in their rented family home in the Sydney suburb of Newtown.

They went about their normal day, playing outside and visiting a neighbour from whom they had taken to begging for food. Around mid-morning the youngest, four-year-old Mervyn, went home. In an upstairs bedroom lay the bodies of his mother and father. Their throats had been slashed with a razor.

This crime is the thread stitching together the tapestry of Tanya Bretherton’s latest book, The Suicide Bride. It’s a fine piece of work, but reviewing it as crime-writing poses challenges.

Described on the cover as “a fascinating and chilling true crime story,” the book is both more than this and – in certain ways – less. Historical true crime, as a genre, offers particular challenges. A writer is limited by the contemporary source material, itself constrained by attitudes and practices of the times.

It’s giving away no more than does the publisher’s blurb to reveal that Mervyn’s father, Alicks Sly, had killed his wife Ellie, before slashing his own throat.

Devotees of classic true crime may pick up this book expecting a full explanation of the dynamics which led to the couple’s deaths – and certainly an answer to the disturbing question of whether, and why, Ellie might have willingly allowed her own killing. Given the constraints, Bretherton does as well as anyone could on these issues. She describes the crime scene in detail, using contemporary accounts by journalists and police. She explores what is known of the personalities and behaviours of the dead couple.

But her exposition necessarily leaves key questions unanswered, and by itself would make for a slender volume indeed.

Fortunately, Bretherton has other strings to her bow.

Though currently a freelance writer/researcher, she holds a doctorate in sociology and had an earlier academic career. The strength of The Suicide Bride lies in her meticulous exploration of the crime’s social context.

Each element surrounding the deaths – the police investigation, the family’s economic circumstances, the consignment of the brothers to an orphanage – is a jumping-off point for exploring some aspect of early 1900s life.

This approach yields fascinating bits of information. For example, while Sydney in 1904 was at “many critical turning points” – on the cusp of transitioning from telegraph to telephone, from gas to electricity – Bretherton reminds us that horse manure collection was still a vital city service.

The mysterious death of the couple’s youngest child – it may have been infection, accident or murder – prompts a discussion of the deadly health hazards households faced. Diptheria and typhoid were problems. So was bubonic plague, which arrived in Australia in 1900, prompting energetic measures by the Board of Health to eradicate rats. Bretherton notes dryly that the distribution of free rat poison, along with tips on making it palatable –spreading on bread, mixing with butter – gave people all they needed to rid their homes of unwanted pests. Animal or human.

Bretherton touches on attitudes linking crime to supposedly hereditary “feeblemindedness” or “moral insanity,” mourning rituals (covering mirrors, bandaging the heads of the dead to prevent unseemly gaping of the jaw), and embroidery traditions brought to Australia by Irish immigrants.

But for me, the stand-out chapter is “Marriage, murder and meteorology.”

Here, Bretherton explores domestic violence, noting that “morbid ceremonies for suicide brides were held every month of 1904 in every Australian state.” To cite but one of her deeply-revealing examples: after eighty-year-old James Horner shot dead his much younger wife, a newspaper report was headlined “Wife murder and suicide: a happy home (my italics) broken up.” Words fail.

This book may not appeal to every true-crime fan. But that’s no reflection on Bretherton’s writing.

Her 2018 book, The Suitcase Baby, was shortlisted for the Ned Kelly Award. The narrative arc in that work benefited from genuine suspense – whether a mother would hang for killing her baby – allowing a delicate balance between crime and broader context.

With The Suicide Bride, Bretherton faces a harder task. Both victim and killer are dead from the opening chapter, and what has happened – to the extent we can know it – is clear from early on.

Bretherton’s style is accessible, and she has the gift of bringing to life potentially dry material about the mores and practices of the past.

So if you are happy to take your true crime supplemented with a generous helping of social history, this one is worth a read for the domestic violence chapter alone.