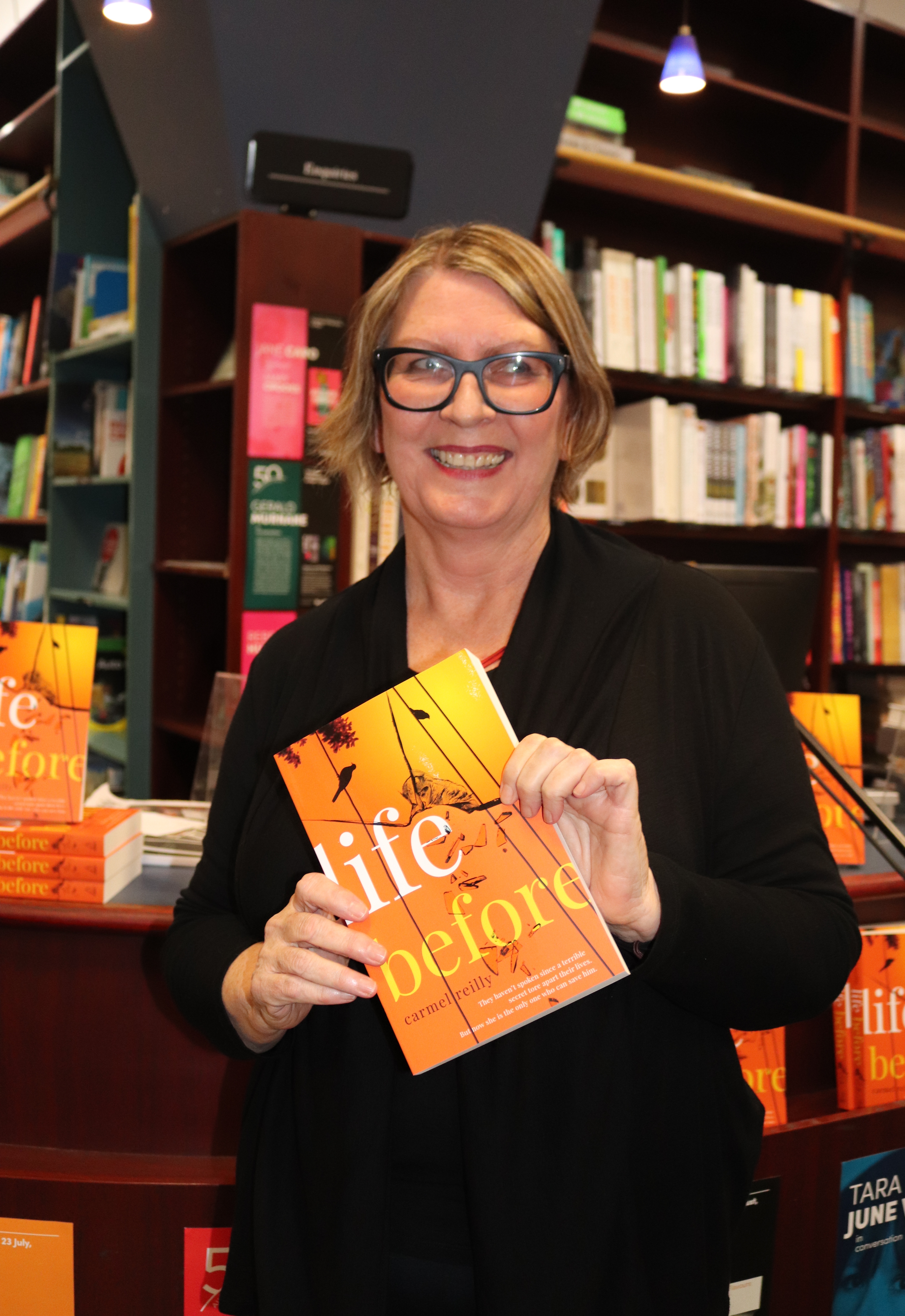

I’m a children’s educational writer by trade, but recently I’ve just released a crime-ish adult book, Life Before. People ask me how the two types of writing mesh together? Has being an educational writer been a help or a hindrance to writing for adults? My answer to that is that my background is probably more of a help than you might imagine, but in the end writing for adults requires shifting into a different gear.

I’ve been working in the educational writing field for almost two decades. It’s a fantastic industry to be in. I’m incredibly grateful to be able to work fulltime as a writer and actually make a living from it. Most of what I write is short. My ‘books’ (Amazon categorises them as pamphlets!) are usually twelve to thirty-two pages long and might contain anything from twenty words to a thousand. Sometimes I write longer ‘readers’ for older children, which range from about 5,000 to 20,000 words. I’ve also written numerous non-fiction and informational books.

So how has this writing helped me with adult writing work? My first (and best) writing teacher was a man who’d had a former life as a journalist, editor, and author of non-fiction and crime. He used to say that the most important attribute a writer could have was ‘bum glue’. It’s not an elegant term, but it is one that has stuck with me (pardon the pun) over the years. Essentially, he was talking about persistence. Write, write, write. Practice doing anything and everything. So what if your piece isn’t that good? Keep at it. Re-hone. Start all over again if needs be. As a younger writer I invariably gave up when what ended up on the page was not the glowing prose that I imagined it was going to be, or when I didn’t know where to head next with a storyline. It took me a long time to realise that a perfect—or even adequate—story didn’t come fully formed; that it needed to be crafted and that craft had to be persistently developed. Having to write for a living and writing to deadlines has really focused my writing, made it an everyday thing. Writing small do-able educational pieces was, and still is, a good way for me to build up stamina and momentum.

From time to time I’ve had ‘poor you’ vibes from people when they hear what I do. The sense that you can’t just go freeform on your projects is a thing of horror for many (often aspiring) writers. The idea that you have to conform to the stuffy norms of the education world which can dictate not only what sorts of words are used at what level but what kind of notions are discussed. And it’s true that there are often restrictions in these texts, but that doesn’t mean you can’t learn a lot from writing them or, indeed, have fun with them. Working out how to construct sentences with a simple vocab, concentrating on making every word count, thinking hard about how to create a narrative arc in (at the extreme) under fifty words—all of these challenges are skill-building, and some of them not so different from exercises you might encounter in creative writing classes. Higher-level, longer kids’ books also have the same kind of requirements as all works of narrative fiction: plot, setting, characterisation, point of view, voice, tense, pacing. Perhaps one major deviation is that educational publishers always want a synopsis or plot outline, which I often find extremely hard to deliver. In my own writing, while I use plotting to some extent, I know from experience that storylines never quite go to plan.

So, in terms of the basics of writing, working in my field has actually been really helpful. But when it comes down to the finer points of creating longer pieces of grownup fiction, it’s a different story and that story is all about developing more specific writing craft. A couple of years into my educational writing career (that is, cobbling together enough writing and editing work to scrape by) I went back to my own work with a different eye. I wrote a YA fantasy novel, started a crime novel (since morphed many times and still unfinished) and produced a number of short stories—one of which became the basis for my recently released novel Life Before. Along the way, a lot of ‘darlings’ were killed (many are still knocked off regularly) and I’ve learned/am learning an enormous amount through the doing and the re-doing. And, of course, the other main mode of learning—the continual reading (and dissection) of other novels.

So, in terms of the basics of writing, working in my field has actually been really helpful. But when it comes down to the finer points of creating longer pieces of grownup fiction, it’s a different story and that story is all about developing more specific writing craft. A couple of years into my educational writing career (that is, cobbling together enough writing and editing work to scrape by) I went back to my own work with a different eye. I wrote a YA fantasy novel, started a crime novel (since morphed many times and still unfinished) and produced a number of short stories—one of which became the basis for my recently released novel Life Before. Along the way, a lot of ‘darlings’ were killed (many are still knocked off regularly) and I’ve learned/am learning an enormous amount through the doing and the re-doing. And, of course, the other main mode of learning—the continual reading (and dissection) of other novels.

As for the hindrances… For me the biggest drawback is that when I work all day writing, I don’t necessarily have the time or energy to do my own stuff—and writing seems to use up a particular kind of mental energy. (Well, that’s my excuse, anyway.) I also find it hard to switch between projects as the headspaces are quite different. I tend to wait until I have gaps in my schedule, which at times are few and far between.

All-in-all though, I count myself extremely lucky to have the day job I have. I’m not sure that without it I would have discovered the bum glue need for my own projects. And in the end, it’s that persistence that is what enables you to bring everything else together.

Carmel Reilly writes for children and adults. Her debut crime-influenced novel Life Before is published by Allen and Unwin.

Carmel will speak on Sisters in Crime’s panel, Friday 26 July 26, 8pm– The Rising Sun Hotel, 2 Raglan Street and Eastern Road, South Melbourne. Click here for more details and to book.